Queen Victoria was the world’s most prolific drug dealer. This is why you should run your business like her

Yes, you read that right: the prim-and-proper Queen Victoria – matriarch of the British Empire – was arguably the biggest drug dealer in history.

In the mid-1800s, her empire ran a massive opium trafficking operation that made Pablo Escobar and El Chapo look like small-time corner dealers. The scale was staggering: at its height, opium sales made up as much as 15–20% of the British Empire’s annual revenue.

The profits from this state-sponsored drug ring helped fund Victorian Britain’s global dominance, and the Queen never faced a day of legal trouble for it – when you are the law, you don’t worry about the law. As one historian wryly noted, Victoria didn’t fear prison because “everyone with the authority to punish drug crimes was already on her payroll”.

Sounds insane? It was. But behind this wild history are serious business lessons. Queen Victoria’s no-nonsense exploitation of a market opportunity (however immoral) offers a masterclass in strategy, supply chain control, market expansion, and ruthless execution. Strap in – we’re about to distil how a 19th-century monarch built a drug empire and what you can learn from it to grow your own (legal) business empire.

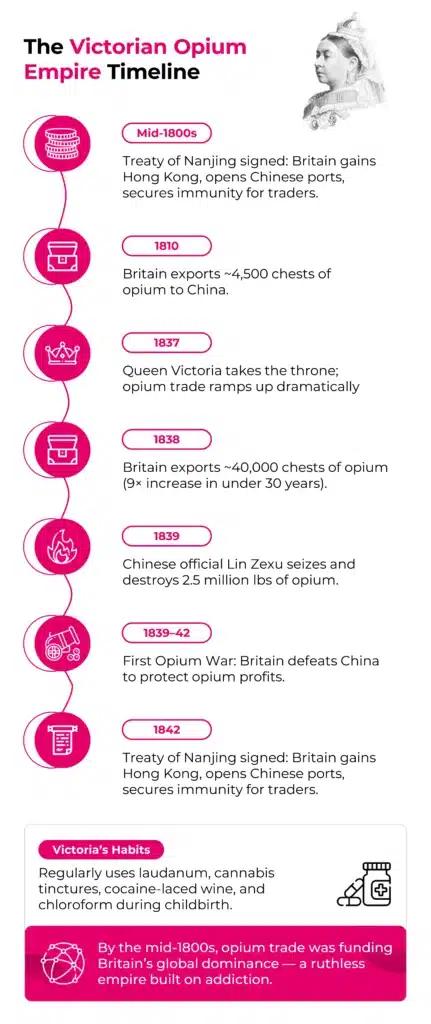

The Victorian Opium Empire: How a Queen Became a Kingpin

In Queen Victoria’s early reign, Britain faced a crippling trade problem. The British were obsessed with Chinese tea, silk, and porcelain – an average London household spent 5% of its income on Chinese tea – but China didn’t need much from Britain.

Silver was flowing out of British coffers to pay for all that tea, and China was getting rich while Britain ran a huge trade deficit. The British were desperate for a solution – “something, anything, that Chinese people craved” as much as Britons craved tea. Enter opium.

Opium was Britain’s magic bullet. It checked all the boxes of a blockbuster product: cheap to produce, high demand, high pricing power, and utterly addictive. The British East India Company had already established a monopoly on opium production in British-ruled India (especially Bengal) by the late 18th century.

Under Victoria’s rule, they ramped it up to industrial scale. Mountains of opium paste were processed in Indian factories and packed into chests for export. (In one East India Company factory in Patna, India, workers stacked huge piles of opium “cakes” – literally tons of product destined for Chinese markets).

With the supply secure, British merchants smuggled opium into China in ever-growing quantities.

And grow it did – explosively. Britain had been trickling opium into China for years, but once Victoria took the throne in 1837, the trade grew exponentially. In 1810, Britain shipped about 4,500 chests of opium per year; by 1838 it was 40,000 chests – nearly a 9× increase in under 30 years.

Chinese demand skyrocketed as millions of people became hopelessly addicted. What started as a recreational vice turned into widespread dependency – users would do anything to keep the pipe lit.

From a business perspective, this was the ultimate customer lock-in: opium’s addictive nature meant inelastic demand (addicts kept buying even at high prices) and a river of silver flowing back to British coffers.

Thanks to this “miracle” product, Britain reversed its trade deficit practically overnight – suddenly, silver was pouring out of China and into British hands. Queen Victoria’s empire was effectively solving its financial woes by creating and selling addiction.

Of course, the Chinese government was not amused. Opium was officially illegal in China (for obvious reasons), and by the 1830s the Qing Dynasty moved to crack down on the narcotics crisis devastating their society. Lin Zexu, a high-ranking official, pleaded with Queen Victoria in a letter to stop peddling “poison” to his people – pointing out the rank hypocrisy of Britain selling a drug in China that it wouldn’t tolerate at home.

The Queen ignored the letter. When Chinese authorities seized and destroyed over 2.5 million pounds of British opium in 1839, Victoria reacted like any outrageously entitled CEO protecting her cash cow: she declared war.

Thus began the First Opium War of 1839–42 – essentially Britain’s military enforcement of its drug market share. The British Navy and Army (the Victorian “marketing team”) pummeled China’s coastal cities. They slaughtered tens of thousands of Chinese people and decisively defeated the Qing forces.

The resulting Treaty of Nanjing was absurdly one-sided: Britain took Hong Kong, forced open multiple Chinese ports for ongoing trade, and secured immunity for British drug dealers in China. In short, Queen Victoria’s empire literally went to war to protect its drug profits, and it won.

The message was clear – no one would cut off this revenue stream without facing the British Empire’s full fury.

The fallout for China was catastrophic (ushering in what they call the “Century of Humiliation”), but for Victoria’s business interests it was a bonanza. Opium revenue continued to pour in, propping up British finances.

Not only was Victoria the ultimate drug kingpin, she was essentially above all consequences. She never had to answer for the mass death or the ethics of pushing narcotics. On the contrary, she reaped the rewards openly – funding her government with drug money and basking in imperial power.

Queen Victoria also indulged personally: she started every morning with a “refreshing” swig of laudanum – a potent opium tincture – and even enjoyed cocaine-laced wine and cannabis tinctures under medical advice.

By modern standards she’d be a poly-substance abuser, but in the 19th century this was fairly normal among the elite. She literally got high on her own supply, finding chloroform anaesthesia during childbirth “delightful beyond measure”. Talk about product testing!

Grim history, no doubt. But within this story are sharp business insights (minus the grotesque immorality) about how to dominate a market. Here are the key lessons Queen Victoria’s drug empire can teach you about running a successful business:

Lesson 1: Find an Insatiable Market (and Solve a Big Problem)

Queen Victoria’s regime faced a major economic problem (the trade deficit with China) and solved it by exploiting an insatiable market need. The Chinese didn’t think they needed opium – until they tried it. Once they did, the product created its own demand.

Opium was a painkiller and mood-altering escape that people got hooked on almost immediately. From a business perspective, this was genius: it turned China’s population into repeat customers by the millions. Britain found a product the customer couldn’t stop buying.

Every entrepreneur should seek a product or service with “addictive” appeal (in a legal, ethical way of course!). What’s the pain point or desire in your market that isn’t being met? How can you fulfill it so well that customers keep coming back on their own?

In Victoria’s case, the British desperately needed something to trade; opium’s “super addictive” nature guaranteed customer retention and solved Britain’s tea addiction problem in one stroke. The lesson: identify a deep, pressing need (or create one) and meet it with a product so compelling that it practically sells itself.

When your offering fixes a big problem or delivers pleasure people crave, you won’t need to chase customers – they will chase you. (Just make sure your solution actually helps people, rather than destroying lives. Common sense, right?)

Lesson 2: Monopolise the Supply Chain

Victoria’s empire didn’t leave their “secret sauce” to chance. They controlled the supply from end to end.

The East India Company locked down opium production in India through a state-sanctioned monopoly They grew tons of opium in Bengal and ensured no one else could source that quantity or quality as cheaply. By owning the supply, they controlled pricing and quality – effectively cornering the market.

Even the distribution was tightly managed: the British auctioned opium in Calcutta to licensed traders and orchestrated a giant smuggling network into China. This vertical integration meant huge profit margins – Britain was buying opium dirt-cheap from Indian farmers and selling it at sky-high prices to Chinese addicts.

For your business, the takeaway is to own and control as much of your supply chain as possible. Whether it’s manufacturing your product, securing exclusive deals with suppliers, or developing proprietary technology, a degree of monopoly power is a huge business advantage.

When you control the key inputs or distribution channels of your industry, you gain pricing power and resilience. Queen Victoria’s operation had virtually no competition in the opium trade for decades – they dictated terms.

Similarly, ask yourself: What critical part of my product or delivery can I dominate? It might be intellectual property, supply contracts, distribution networks, etc. By building your “moat” around supply, you make it hard for competitors to undercut you.

Just as importantly, you can maintain quality and consistency. Victoria’s empire wasn’t at the mercy of some third-party supplier; they were the supplier. In short, be the East India Company of your niche – don’t just play in the market, own the market.

Lesson 3: Scale Aggressively When Opportunity Knocks

Once product-market fit was achieved (Chinese demand for opium exploded), Queen Victoria’s team hit the gas. They scaled the opium trade with a vengeance. We’re talking 10× growth in under thirty years – from a few thousand chests a year to tens of thousands.

Sure, that’s a slow burn by today’s standards, but back then – without the internet, digital ads, or global supply chains – that kind of scale was basically warp speed.

This hyper-scaling not only maximised profits, it also entrenched their dominance before anyone (like the Chinese government or rival traders) could react effectively. By the 1840s, opium was up to 20% of imperial revenue – a cornerstone of Britain’s economy.

The British basically said “we’ve got a money printer here, let’s run it 24/7” – and they did.

The business lesson is simple: when you find a winning formula, pour fuel on the fire. Scale up fast to seize the market. That might mean ramping up production, hiring en masse, expanding to new regions, or heavily reinvesting profits into growth.

Speed is often the difference between market leaders and also-rans. Victoria’s empire saw a chance to turn a profit and flooded the market before China could contain it. By the time the competition or regulators wake up, you’ve already locked in your customer base.

In modern terms, this could be capturing users in a new app category, being the first to mass-produce an innovation, or aggressively acquiring competitors.

As a caution: scale smart – don’t compromise quality or ethics – but do scale. If you don’t, someone else will. The opium trade was a gold rush and Britain moved decisively to stake their claim. Likewise, when you identify your “opium” – that product or service everyone will want – be ready to go all-in and grow fast. You likely won’t get a long window before the opportunity closes.

Lesson 4: Defend Your Turf Relentlessly

Perhaps the starkest lesson from Queen Victoria’s playbook is ruthless market defence. When the Chinese authorities finally tried to shut down her biggest revenue stream, Victoria literally went to war to defend her business.

Now, in today’s business world, we (thankfully) don’t use gunboats and cannons against our competitors or regulators. But the principle of unyielding defense of your market share is critical. Are you willing to fight tooth and nail to keep what you’ve built?

In Victoria’s case, the “competitor” was the Chinese government threatening to cut off her access to customers. She responded with overwhelming force, destroying the competition’s ability to operate. In business, defending your turf might mean outpricing competitors, doubling down on innovation, engaging in legal battles, or lobbying against unfavourable regulations.

It’s about not rolling over when someone tries to muscle you out. If you know your product is valuable and your position is justified, play hardball. Think of how modern companies defend market share – they’ll file lawsuits over IP theft, run massive ad campaigns to outshine a new rival, or rapidly iterate to render a competitor’s feature obsolete.

Whilst Queen Victoria’s scorched-earth response – killing tens of thousands and imposing a humiliating treaty – may have been overkill (and not great on the morality scale), but it did remove obstacles to her market. The takeaway for you: protect your business aggressively.

Don’t let a newcomer poach your best clients without a fight, don’t allow complacency to give someone else an opening. Be it through superior customer service, better marketing, or yes, lobbying for your interests, you must be prepared to stand your ground.

Business can be brutal; if you’re passive, more determined players will eat your lunch. As Victoria showed, winning often goes to whoever is most relentless. (But hopefully you will draw the line before gunfire! An aggressive lawyer in your corner is usually enough to do the trick.)

Lesson 5: Influence the Rules

One reason Victoria’s narcotics empire thrived is that she was effectively above the law. It’s easy to run a drug cartel when you’re also the queen writing the laws – no risk of jail time for Her Majesty. As noted earlier, all the people who could arrest or charge her were on her side.

This highlights a savvy (if at times shady) strategy: control the regulatory environment to favour your business.

In today’s terms, this means playing the legal and political game to your advantage. You may not be a monarch, but you can still influence the “rules of the game.” Big companies do this all the time through lobbying, forming industry coalitions, or setting de facto standards.

Is there a regulation that hampers your industry? Perhaps you can join forces with others to get it revised. Are there certifications or standards that, if met, would give customers confidence? Push to make those standard – and be the first to exceed them.

Even on a smaller scale, understanding the law can help you exploit opportunities your competitors are too timid to touch. (For example, finding legal loopholes or incentives for tax, zoning, subsidies, etc., that give you an edge.)

Queen Victoria literally dictated the terms under which her business operated – imposing “free trade” at gunpoint and ensuring British officials had immunity in China. In business, you sometimes need to shape the narrative and rules in your favour.

Maybe you champion a new industry guideline that your product already meets. Maybe you lobby for consumer protection laws that your high-quality business will benefit from while fly-by-night competitors get squeezed out. It’s about being proactive with the system you operate in.

Don’t be a passive player subject to every external rule – wherever possible, try to influence policies, public opinion, and industry norms to align with your business’s strengths.

When you succeed, you’ll find that the very structures of the market start working for you, not against you. (And if you can’t change a rule, at least learn it inside-out so you can navigate it better than anyone else.)

Lesson 6: Believe in Your Product (But Maybe Don’t Get High on Your Own Supply)

One oddly amusing aspect of Queen Victoria’s story is how much she personally loved the product. The Queen was not only a pusher of drugs, but an avid customer as well.

She drank laudanum (opium tincture) every morning to pep herself up, gobbled cocaine-infused gum for her dental pain, smoked cannabis extracts for menstrual cramps, and praised chloroform anaesthesia to the high heavens.

As one historian put it, “Queen Victoria, by any standard, loved her drugs.” There’s a business joke here: she had unshakable confidence in her product – so much that she used it liberally.

In modern entrepreneurship, we often talk about “eating your own dog food,” i.e. use your product as a user would. You should absolutely believe in what you sell. If you don’t have faith that your offering is valuable, why should anyone else?

Queen Victoria took this to an extreme, but it underlines the point: she was all in on the value of her merchandise. When you genuinely stand by your product, two things happen.

First, you intuitively understand the user experience and can improve it (Victoria literally felt the effects of her goods, for better or worse).

Second, your conviction becomes contagious – customers, investors, and employees sense your authenticity and passion. Great entrepreneurs from Steve Jobs to Elon Musk have famously been users of their own products and evangelised them ardently.

So ask yourself: do I love my product or service enough to be its biggest user and cheerleader? If not, either improve it until you do or reconsider what you’re selling. Authentic enthusiasm can’t be faked.

Now, a caveat: unlike Queen Vic, please stay objective – don’t get “high” on hype alone and ignore faults. And certainly don’t become the literal #1 consumer of your inventory if it’s, say, whiskey or donuts – that might end badly.

The goal is to maintain product zeal tempered with clear-eyed quality control.

Victoria’s haze of self-medication may not have improved her leadership, but her genuine belief in the power of her product helped drive her empire’s success. In your case, strive for that unshakeable belief in what you offer (minus the actual opium habit).

Conclusion: Seize the Market, Rule the Game

Queen Victoria’s legacy is a mixed bag to say the least – she built an empire and enriched her nation, but through some of the most predatory business tactics imaginable. You should NOT emulate her ethics, but you can learn from her ruthless effectiveness.

To recap, running your business like Queen Victoria means:

- Identify a product with irresistible demand

- Control your supply chain and scale it to the moon

- Fiercely protect your market

- Shape the rules in your favour

- Believe wholeheartedly in what you’re selling.

And if you need the capital to make those moves, Borrow From Me can help with fast, flexible business loans in the UK.

These principles, applied ethically, can set you apart from the timid players in your industry. History shows that boldness and strategy can create empires. Fortunately, you don’t need to sell drugs or colonise anyone to build your own business empire. Take the underlying lessons from Victoria’s story – the focus, the audacity, the strategic monopolisation – and apply them to your venture in a way you’ll be proud of.

The business world can be tough, but with a No Bollocks approach and a willingness to do what others won’t (again, legally!), you can dominate your market. That’s where Private Coaching or Consult With Me comes in, giving you the clarity, strategy, and execution to scale with confidence.

Now, it’s your turn. If this breakdown hit you, imagine applying lessons like this directly to your own business — with me in your corner and a network of hungry entrepreneurs beside you. Whether it’s expanding your network through Introduce To Me, forging smart partnerships via Invest With Me, or booking me to share these insights at your next event with Book Me As A Speaker, you’ll have the tools and connections to accelerate growth.

So, if you’re serious about building an empire of your own, don’t just nod along to history lessons — join us today. Let’s turn these principles into action, and make sure your name ends up on the winning side of history.